Chamas for Change Gender and COVID-19 Matrix

The ‘Chamas for Change: A gender-responsive and microfinance-based approach to empowering women’ is an intervention and applied research project based in Trans Nzoia County in Kenya. It is part of a community-based programme in Western Kenya that was established in 2012 to support rurally residing pregnant women, adolescent girls, and mothers during the first 1000 days of their child’s life. To strengthen maternal and child health while supporting economic empowerment, the programme, led by community-health promoters, creates opportunities for group-based health education, peer support, and microfinance. Project evaluation indicates that participation in Chamas contributes to positive health outcomes associated with increased antenatal care visits, delivery by trained healthcare workers, exclusive breastfeeding, family planning uptake and infant and child immunization. Chama women also have more peer support including through relational accountability and agency in problem solving amongst themselves and the community at large. Chama women have reported feeling more empowered to care for themselves and their families. There are currently 659 Chama groups with 7,274 women participating across Western Kenya and over 17,000 members who have graduated from the programme since its inception.

*Chama is Swahili for ‘group’. Gaining momentum from the 1980s through the philosophy of harambee (community self-help), Chamas are self-organizing micro-saving groups that continue to be popular across Kenya particularly among women

- COVID-19 Illness

- COVID-19 Risk

- COVID-19 Health Impacts

- COVID-19 Social Impacts

- COVID-19 Economic Impacts

- COVID-19 Security Impacts

How did communities experience COVID-19 illness?

What was the experience seeking COVID-19 treatment, testing, vaccination etc.?

-

What has what?

E.g. income, assets, information, knowledge (education), mobility, social networks, timeHow did gendered access to resources shape the distribution of risk of COVID-19 illness and access to treatment?

Cost of COVID-19 treatment deterred those with limited resources from utilizing health facilities: Some used home remedies and traditional healers

Most people with COVID-like symptoms chose to quarantine at home but some homes were overcrowded and hence insufficient in preventing spread of infection within households

People dependent on daily wages for sustenance were unable to follow quarantine measures even when they had COVID-like symptoms

Individuals perceived as most affected by COVID-19 illness and death included older people, those with chronic health conditions or comorbidities, people living with disability, and pregnancy women

-

What has what?

E.g., paid and unpaid labourHow did gendered labor and roles affect people’s treatment of COVID-19 infection?

Community health promoters (CHPs) were central to connecting people in isolated settings to COVID-19 testing and treatment through information sharing and referral services: Most CHPs are women

Women were more likely to discharge themselves from quarantine centers in health facilities to attend to care responsibilities at home

-

How are values defined?

E.g., expectation on appropriate behaviour, attitude of influence

How do norms and beliefs affect people’s treatment of COVID-19 infection?Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, people typically sought treatment in health facilities when their conditions became critical; this health-seeking behavior was mirrored in seeking COVID-related treatment

Women are perceived as more likely than men to seek treatment when ill; women were more likely to seek COVID-19 information and referral from community health promoters

COVID-19 was perceived as deadly and easily spread: Individuals infected with COVID-19 were stigmatized; some people did not test for COVID-19 or share test results for contact tracing due to stigma

Fear of death upon hospitalization for COVID-19 treatment after testing positive deterred some people from going for testing when they experienced COVID-like symptoms

Fear of visiting health facilities contributed to some people seeking herbal remedies and traditional healers when they experienced COVID-like symptoms

-

Who decides?

Power distribution & negotiation at household/ community level

Who made decision on treatment of COVID-19?Within households, men were more likely to make decisions on where to seek COVID-19 treatment if there were financial implications

-

How is power structured?

Leadership opportunities, education, employment, ownership/inheritance rights, infrastructureHow did government institutions and law support COVID-19 treatment? Was there a balanced gender representation within related government structures?

Quarantine centers were poorly resourced contributing to unsanitary conditions and inadequate food for COVID-19 patients; some people discharged themselves because of discomfort and hunger. The government increasingly encouraged people to quarantine in their homes due to resource constraints

All counties in Kenya were required to have a capacity of at least 300 beds for isolation and treatment :Trans Nzoia County drew from the Ebola epidemic experience when setting up isolation centers; however, there was still a lack of clarity on how to operate such centers

Community health promoters (CHPs) faced restrictions and fear in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in communities due to police enforcement of public health measures without acknowledgement of CHPs role in COVID-19 response

Random testing campaigns were undertaking within communities to bring COVID-19 services closer to the people

Trans Nzoia County ran a 24-hour crisis line for COVID-19 reporting to support contact tracing work

Balanced gender representation was noted in COVID-19 decision-making bodies; this included the emergency committees and technical working groups who provided a roadmap on COVID-19 response and coordinated with the National Pandemic Response Committee

Government bureaucracy and mismanagement of COVID-19 resources was noted to delay response and undermine efficiency

At the start of the pandemic, there was only one COVID-19 treatment facility in Trans Nzoia County (at Mt. Elgon Hospital) resulting in delays in referral; services were later decentralized to increase access

Initially Trans Nzoia county did not have capacity for COVID-19 testing and had to transport samples to neighboring counties causing delays in seeking treatment

Health care facilities in Trans Nzoia County were not well equipped to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic; there was a limitation in intensive care units, oxygen cylinders, ambulances, and laboratories to facilitate COVID-19 testing

In the first wave of the pandemic, Trans Nzoia county had limited resources to respond to COVID-19 infections but increased its capacity for testing, quarantine, and treatment

Lack of an emergency fund and a pandemic response plan delayed COVID-19 response e.g., the County lacked capacity for testing, isolation, treatment, and vaccination: County resources were reprioritized to respond to the pandemic by shifting funding from other departments to the health department and from non-COVID health budget and infrastructure to COVID response. Reallocation of funding required an approval process that took at least three months.

Collaboration between the government and private healthcare facilities was slow and limited

What is the community perception about COVID? E.g., not believing its existence

How did people respond to the pandemic? e.g., attitudes/actions towards public health measures

What is the perception on who is most or least at risk & why?

What situations presented higher/lower risks? E.g., urban-rural movements

-

What has what?

E.g. income, assets, information, knowledge (education), mobility, social networks, timeHow did gendered access to resources shape the distribution of risk of COVID-19 infection?

Those with limited resources to afford COVID prevention supplies such as masks, hand sanitizers and soap were at higher risk of infection: Women are more likely to experience poverty due to gendered traditions that limit their access to assets and economic opportunities

People with COVID-like symptoms chose to quarantine at home but some homes were overcrowded and hence insufficient in preventing spread of infection within the household

Influx of people from urban areas and cities due to economic hardship increased risk of exposure to COVID-19 in communities

Limited knowledge on the COVID-19 virus, how it spreads, and how to reduce risk resulted in high risk of COVID-19 infection during the first wave of the pandemic

Increased COVID-19 awareness through educational campaigns by community health promoters (CHPs) and Chamas (self-empowerment groups) reduced risk of COVID-19 spread in communities

Corporate and NGO donations of PPE supplies and washing stations helped communities reduced risk of COVID-19 spread

Provision of washing stations in churches, supermarkets, and businesses helped reduced risk of COVID-19 spread; some churches and facilities also had thermal guns

-

What has what?

E.g., paid and unpaid labourHow did gendered labor and roles affect people’s risk of COVID-19 infection?

Perception of risk of COVID-19 infection due to gendered labour and roles was mixed

Gendered division of labour placed greater risk of COVID-19 infection on women as carers in the health care system and within communities and homes*Health care providers and community health promoters are mostly women; the latter were mandated to conduct contact tracing and facilitate quarantine in community

Gendered roles within the household (i.e., women doing domestic and care work at home and men seeking income outside the home as the breadwinner) placed men at higher risk of COVID-19 infection

Gendered roles in the labour market contributed to a nuanced distribution of COVID-19 risk e.g., women working in markets and men in motor cycle transportation experienced similar risk factors

-

How are values defined?

E.g., expectation on appropriate behaviour, attitude of influence

How do norms and beliefs affect people’s risk of COVID-19 infection?Gendered norms and beliefs that shape practices placed men and boys at higher risk of COVID-19 infection than women and girls:

*Women are expected or perceived to be more cautious and more likely to follow public health directives than men

*Girls are expected to follow parental guidance and perceived as “easier to control” than boys: Girls were more likely to stay indoors following public health guidance

*Women are expected or perceived to have better hygiene practices than men

*Men are expected to socialized with friends and acquittances outside the home even after work: Men socialized in drinking dens (pubs) where public health measures were not enforced

Some people chose to ignore existence of COVID due to social disruption posed by public health measures such as limited socialization and economic opportunities

Stigma associated with COVID-19 deterred people from sharing information about their symptoms making contact tracing efforts difficult

Mistrust towards government made some people not believe in the existence of COVID or follow associated public health measures

During the pandemic, improved hygiene was noted among men such as washing hands more frequently

People feared going into quarantine centers with healthcare facilities because of fear of COVID-19 spread or severe COVID-19 illness

-

Who decides?

Power distribution & negotiation at household/ community levelWho made decision on measures taken to prevent the risk of COVID-19?

Both men and women were involved in decision making on measures taken to prevent the risk of COVID-19 at household level. Typically, the father would be more involved in decisions regarding movements outside the home, and the mother ensured improved hygiene measures were followed

At community level, Nyumba Kumi (community policing groups) provided contextualized guidance on how to reduce risk of COVID-19 spread

-

How is power structured?

Leadership opportunities, education, employment, ownership/inheritance rights, infrastructureHow did government institutions and law attempt to reduce risk to COVID-19? How did they contribute to COVID-19 risk? Was there a balanced gender representation within related government structures?

Police enforcement of COVID-19 public health measures in the first waves of the pandemic increased risk of COVID-19 spread

The police, for instance, held in close proximity people found not adhering to curfew or mandate to wear masks

The county government created quarantine centers to facilitate monitored isolation of those infected by COVID-19: The national government mandated all county government to create such centers

Quarantine centers were overcrowded increasing risk to COVID-19 spread

Following initial lack of clarity of how to respond to the pandemic, the national and county government provided information on public health measures and protocols to reduce risk of COVID-19: County government considered guidance from the World Health Organization and the national government

Public health measures mandates and implemented by government included use of masks, curfew, random testing in communities, contact tracing, quarantine requirements, restrictions of movements across counties, closure of markets, disinfecting public places, restrictions on social gatherings such as funerals and church service, among others

The Ministry of Health and county government facilitated training of health care workers and community health promoters on how to reduce individual risk to COVID-19 and facilitate information sharing with the public

County government officials and community health promoters facilitated periodic social mobilization campaigns to publicize information about the COVID-19 pandemic and response measures in communities

Initial delays in test results (as test samples had to be transported to cities with COVID-19 laboratory facilities) increased risk of COVID-19 spread

Lack of an emergency fund and a pandemic preparedness plan delayed COVID-19 response coordination and distribution of adequate PPE

A COVID-19 response committee including actors from various county departments and offices was formed to make decisions and coordinate efforts to reduce risk of, and treat, COVID-19: The committee was only disbanded when COVID was contained within international standards

Corporate, NGO, and UN donations facilitated purchase and broader distribution of PPE help reduce risk of COVID-19 spread

What were the health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and related public health measures?

What was the experience seeking non-COVID health care?

-

What has what?

E.g. income, assets, information, knowledge (education), mobility, social networks, timeHow did gendered access to resources shape the distribution of health impacts of COVID-19?

Adolescent health was affected by the pandemic as services to this group was limited due to closures of youth friendly facilities and health centers e.g., contraceptive counselling and services, youth friendly HIV clinics. Increase in teenage pregnancy was partly attributed to this gap

Access to antenatal care to pregnant women and girls, and care for women with infants was hindered during the COVID-19 pandemic because of curfew measures which limited movement and transportation options: Decline in immunization was noted at the height of the pandemic

Women and girls experiencing pregnancy but with limited access to resources to access private health care experienced disruption of services in government and community health clinics due to reduced services as resources were reallocated to COVID-19 response

People with chronic conditions including HIV experienced limited access to services and medication during the pandemic due to reduced health services, curfew measures, limited transportation options, and mandatory testing and vaccination: Health care visits by those with comorbidities was noted to have declined at the height of the pandemic; more resourced individuals utilized private health facilities and pharmacies

Mental health and wellness was noted to have generally declined during the pandemic. Research participants highlighted depression, stress, emotional destabilization, suicidal ideation, suicide, and trauma attributed to isolation, financial impacts, fear and confusion regarding the pandemic, disruption of school and teenage pregnancy

-

What has what?

E.g., paid and unpaid labourHow did gendered labor and roles affect people’s health impacts and how they responded to these impacts?

Health care workers were overwhelmed due to fear of contracting COVID while on duty, and increased workload and work hours without incentives; HCW went to strike during the pandemic limiting access to healthcare in the county. Most HCW are women.

Residents increasingly consulted health care workers within their networks and communities, even those who were retired or unqualified due to limited access to health care in facilities, cost implications of health care, and fear of COVID-19; this became the first line of care for some

Community health promoters continued providing care and referral services in communities through home visits; however, their reach was limited due to restrictions on movement and fear of COVID-19

-

How are values defined?

E.g., expectation on appropriate behaviour, attitude of influenceHow do norms and beliefs affect people’s COVID-19 health impacts and how they responded to these impacts?

Men are perceived as less likely than women to seek health care when feeling unwell; this can be attributed to a belief associating men with bravery and hence seeking help as weakness. However, the pandemic created an environment where all people reprioritized their health

Normalization of hygiene routine such as regular hand washing, including among men, was noted to have reduced incidents of contagious infections and illnesses

There was general fear of going to health facilities due to fear of COVID-19 infections or forced quarantine especially at the height of the pandemic: Women and adolescent girls feared seeking family planning services, antenatal care, and infant immunization; some visited facilities early in the morning to avoid crowds; other pregnant women and girls opted for traditional birth attendants and home deliveries

The relationship between community health promoters (CHPs) and community members was strained when it came to health care provision because CHPs were perceived as being agents of the government due to their enforcement of COVID-19 quarantine and contact tracing

-

Who decides?

Power distribution & negotiation at household/ community levelWho made decision on non-COVID health care?

Reduced health clinic hours limited the choice of adolescent mothers on when they seek health care in efforts to shield themself from social stigma; this affected their access to reproductive and maternal health care

Civil society organizations were at the forefront of advocating for adolescent health considerations during the pandemic as health resources were reprioritized to address COVID-19 response

Civil society organizations ran programs to support health and wellbeing of women and adolescents, including education on how to prevent COVID-19 infection

When it came to health access, CSOs prioritized adolescent girls, but also acknowledge similar challenges faced by adolescent boys such as isolation

-

How is power structured?

Leadership opportunities, education, employment, ownership/inheritance rights, infrastructureHow did government institutions and law affect non-COVID health care access? Was there a balanced gender representation within related government structures?

Trans Nzoia County’s health care system experienced stress in expanding to COVID-19 care and treatment while trying to maintain other health services. With a population of about 1 million, the county has one major hospital (Kitale County Hospital), a sub-county hospital in each subcounty, about 26 health centers and 76 dispensaries, and community health workers: Residents are sometimes referred to neighboring Moi Teaching Referral Hospital. During the pandemic, limited resources were redirected to COVID-19 response.

Reprioritization of health care resources, including funding, infrastructure and health workers, limited provision and access to non-COVID health care such as maternal health care.

Gains on adolescent-specific health care were lost during the COVID-19 pandemic; discussions to include a budget line for adolescent health in the health or gender departments were halted. Youth-friendly health facilities or youth centers within facilities which were opened before the pandemic were closed or turned to COVID-19 wards or isolation centers during the pandemic. Adolescent health programming including reproductive health clinics, family planning services, HIV clinics and anti-natal care became limited

Public health measures in hospital settings such as required testing and vaccination made health care inaccessible to those who were hesitant to such measures; Health care facilities mandated use of masks, provided hand washing station, and enforced social distancing during the pandemic to reduce risk of COVID-19 spread

At the national level, the Menstrual Hygiene Management Act and the National Reproductive Health Policy were adopted in 2020 and 2022, respectively; these policies have become platforms for officials and civil society organizations to push for adolescent health initiatives in Trans Nzoia County

Lack of policies and structures aimed at addressing adolescent health left little room for mitigating adolescent health risks during the pandemic. Need for policies, programs, and funding for pandemic or emergency readiness to address needs of adolescent girls and other marginalized community members was noted

Access to medication was limited by constraints placed on frequency and hours of visiting health care facilities as well as supply chain disruption. Some health care facilities supported patients by providing medication for longer periods and accommodating alternative arrangement for refills for those with chronic conditions such as scheduled patient pick-up and allowing relatives to pick up medication on behalf of patients

Donor funding for health care and medication (e.g., from USAID) was noted to have reduced highlighting a need for the county government to increasingly be self-reliant to reduce gaps in health care provision

Over the course of the pandemic, the county’s health department enhanced their capacity for emergency preparedness with enhanced health care infrastructure (e.g., ICU facilities) likely to have longer-term effects

Patriarchy in health care profession (re. male doctors, female nurses) was noted to have been replicated in pandemic response structures where mostly doctors were in top decision-making positions in health-related technical working groups. The Trans Nzoia County RMNCAH (Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Children and Adolescent Health) technical working group, for example, had limited women representation, most of whom represented the gender and social works departments. Gender representation was noted to have improved following a gender training session, where even the youth, people living disabilities, and civil society organizations were included

Pre-established technical working group structures weakened during the pandemic due to budgetary constraints resulting from reallocation of resources to COVID-19 response; the number of working group members reduced from about 40 members to as low as 10 members weakening inclusion and broader engagement

What were the social impacts of the pandemic & health measures? e.g., isolation, cultural practices

How did people cope with the negative social impacts? E.g., ignore public health measure, phone calls

-

What has what?

E.g. income, assets, information, knowledge (education), mobility, social networks, timeHow did gendered access to resources shape the distribution of COVID-19 social impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

COVID-19 public health measures limited access to social infrastructure that could have mitigated some impacts of the pandemic and contributed to resilience for individuals and communities

Restriction on social gatherings and closure of spaces for social connection and interactions such as churches, schools, sports, youth-friendly health facilities contributed to isolation with negatives effects on people’s wellness; such spaces and connections were noted to be crucial for mental wellness in Trans Nzoia County

When social gathering resumed, positive effects of such resultant social interactions were noted. Chama (support groups) provided avenues for women to share on self-esteem, relationships, and strategies for family planning, and encouraged adolescent mothers to go back to school

Chamas (support groups) were considered by women and adolescent girls a social resource for psychosocial and peer support, and a source of information on responding to COVID-19: Some chamas (support groups) provided transport reimbursement to participants increasing accessibility during the pandemic

Friendships, parental relationships, and marriages became strained during the pandemic due to changes in social interaction among other challenges, with cases of domestic violence reported. Some people and married couples utilized counselling to deal with social impacts of the pandemic; this coping mechanism was, however, inaccessible to those with limited resources

Psychosocial impact of the pandemic among adolescent girls was noted to include stress, disappointment, and suicidal ideation due to conflict with parents, school closure, pregnancy among other factors

Schools were considered safe havens for adolescent girls because of reduced opportunity sexual abuse or interaction; adolescent pregnancies during the COVID-19 pandemic were blamed on school closure and gaps in supervision at home

School closure and adolescent pregnancies during the pandemic contributed to girls dropping out of school and reduced focus on education limiting future socio-economic opportunities for girls

-

What has what?

E.g., paid and unpaid labourHow did gendered labor and roles shape the distribution of COVID-19 social impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

COVID-19 public health measures contributed to a shift in social relationships and gendered roles:

*Lost employment, stay-at-home advisories, and curfews resulted in men being at home for prolonged periods than before the pandemic, with some contributing more to unpaid domestic and care work

*Some women ventured into small business and informal work to fill gaps in household income due to lost formal employment of their male partners; some women became bread winners for the first time

*Some children took on income-generating activities during school closure to contribute to household income and cater to personal needs

School closure necessitated greater parental involvement in children’s education to facilitate homeschooling and online learning; however, parents found it difficult to monitor their children at home given their need to seek an income during the day.

School dropout among adolescent girls and boys was noted to have increased during the pandemic due to lost interest in education following school closures, adolescent pregnancies and associated social stigma, need for paid work, and lack of school fees

Some communities facilitated village schooling where teachers volunteered within their villages and brought together students and taught them during school closure

Adolescent pregnancies in Trans Nzoia County were noted to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. This has been blamed on school closures, reduced supervision of girls, poor parenting, disconnect between parents and children, lack of structure, and isolation due to closure of spaces for mentoring and peer support

As the pandemic progressed, people’s perception towards community health promoters (CHPs) shifted with an increased appreciation of their expertise and contribution to community health; CHPs noted increased compliance by patients their visited

-

How are values defined?

E.g., expectation on appropriate behaviour, attitude of influenceHow did gendered norms and beliefs shape the distribution of COVID-19 social impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

Restriction on funeral and burial ceremonies disheartened residents of Trans Nzoia County; limitation on the number of attendants, short timeline between death and burial, and the hands-off handling of the dead made relatives unable to honor or grant dignity to the dead as required by customs and the bereaved were unable to mourn for their dead accordingly

Family conflict, marriage breakdown, family disintegration, and domestic violence was noted to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic; societal pressure of men to be the bread winner, even during an economic downturn, was noted as a contributing factor

Adolescent mothers and pregnant girls were subjected to social stigma while responsible men or boys were not held accountable; in some cases financial compensation relieved the latter of parental responsibilitiesAdolescent pregnancies contributed to family conflict particularly between the pregnant girls and their parents; associated conflict and social stigma contributed to pregnant girls and adolescent mothers feeling isolated and alone negatively impacting their social life, self-esteem, and mental health

Religious and spiritual practices were curtailed by restrictions placed on social gatherings and church closures at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic; associated practices and ceremonies were noted to provide structure and meaning to people’s lives and improve mental wellness

Social stigma towards those who were infected with COVID-19 virus and fear of infection was noted to have contributed to increased hostility and isolation within communities

Constraints placed on day-to-day social practices that contributed to social connection and harmony such as handshakes and social visits contributed to isolation and loneliness

Chamas (support groups) with financial orientation experienced increased distrust and disagreement among members due to infrequent meetings and financial stress among members during the pandemic

Some noted a positive effect on family relationships and bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic as stay-at-home advisories and curfew forced men to come into the home earlier in the day. Men are socially expected to be out of the home fulfilling their provider role at work and socializing with friends after work; many come into the home at night leaving little time for family bonding

The pandemic was noted to have contributed to harmony in community as government, religious, nonprofit, and corporate organizations came together in support of COVID-19 respond including through food donations; an inter-religious council was formed to support response efforts

Consumption of alcohol and drugs by men was noted to have reduced with closures of social places including drinking dens, curfew measures, and financial constraints; however, consumption among boys was noted to have increased during school closure

Chamas (support groups) with financial orientation experienced increased distrust and disagreement among members due to infrequent meetings and financial stress among members during the pandemic

-

Who decides?

Power distribution & negotiation at household/ community levelHow did the power dynamics within the household shift due to social impacts of the pandemic? Who made decisions regarding how to deal with the social impacts?

Women’s position within the households, as caregivers who spend most of their time within the home, made them best positioned to make decisions on adherence of COVID-19 protocols that contributed to social impacts such as isolation; however, mothers noted their limited control over the movement of their children, particularly boys who are socially expected to spend their day out of the home

-

How is power structured?

Leadership opportunities, education, employment, ownership/inheritance rights, infrastructureHow did government institutions and law contribute to social impacts of the pandemic, and how did they attempt to address these impacts? Is there a balanced gender representation within related government structures?

COVID-19 public health measures such as closures, restrictions on social gatherings and inter-county movement, stay-at-home advisories, and curfews had negative implications on social life, harmony, and connectedness, and customary and spiritual practices

County-level government structures to response to effects of the pandemic and response measures were initially dominated by men but this was noted to have shifted to greater representation of women following gender training; leadership in gender and social services was noted to have balanced gender representation, but some department such as sports remained men-dominated

The COVID-19 response experience increased awareness on the importance of meaningful representation of women and adolescents in technical working groups from county to community level structures; those most affected by pandemics and emergencies were initially left out of decision making

The county government engaged religious leaders (through the interreligious council) in their public health measures involving religious gatherings

Restriction of group gatherings and movement hindered consultation processes between county government and partners; the process of seeking permission to meet was noted to be tedious and booking a meeting venue that supports social distancing was expensive

The county government initiated programs for social supports on wellbeing of women and adolescents, as well as other vulnerable groups such as people living with disability, the elderly, and those living in poverty; in addressing floods that occurred during the pandemic, the government facilitated construction of housing for affected residents

School closures was noted to have been necessary because of overcrowding in classrooms that made social distancing impossible; lack of internet or technology in public schools could not support virtual learning

The Trans Nzoia County Department of Education did not have direct line of communication with parents or communities; they passed information to teachers, who shared with students with the expectation that the educational protocols will be shared to parents. This approach likely made it challenging for parents to seek clarity on how they can support the education of their children during school closures

Working from home (e.g., by telephone) by government officials at the department of social services was noted to have negatively affected service delivery as some issues pertaining community service to the elderly and persons living with disability require face to face; those with limited resources to make telephone calls were likely excluded from service

The experience of government officials responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and flooding emergency increased awareness around the need for pandemic and emergency preparedness, and pre-designed response structures and funding allocation

What were the economic impacts of the pandemic & health measures? E.g., poor health impacting ability to work, loss of work

How did people cope with these impacts? e.g., Chamas, loans, family support

-

What has what?

E.g. income, assets, information, knowledge (education), mobility, social networks, timeHow did gendered access to resources shape the distribution of COVID-19 economic impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

In Trans Nzoia County, men are more likely to be employed in the formal sector, while women are more likely to be employed in the informal sector; both sectors were affected by the pandemic. Those who relied on daily wages (e.g., men boda boda drivers and market women) were particularly affected by public health measures that restricted movement and reduced purchasing power of residents

The poverty levels in Trans Nzoia County were noted to have increased during the pandemic; some families coped by reducing the frequency of the meals from three meals a day to two or less. Dramatic loss of incomes among residents due to layoffs, compulsory unpaid leave, collapse of businesses, curfews restricting business hours and reduced purchasing power was coupled by increased prices of commodities

Limited economic opportunities in urban centers (where men typically migrate for work leaving women to care for their children) contributed to a migration back to rural and remote settings

Populations most affected by poverty resulting from pandemic-related economic downturn included the elderly, widows and orphans

Economic hardship and food insecurity forced adolescent girls to engage in transactional sex to access food and personal hygiene products contributing to pregnancies during school closures

Women who relied on microfinance activities and loans through chamas (peer support groups) were affected due to disrupted chama meetings and activities; some women were able to use these platforms to secure money for food

-

What has what?

E.g., paid and unpaid labourHow did gendered labor and roles shape the distribution of COVID-19 economic impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

There was a perception that women were most affected by COVID-19 economic impacts because of their reliance on the informal sector and micro-and-small businesses which are vulnerable to public health measures that restricted movement and reduced business hours

Reduced employment and income opportunities in the formal sector (dominated by men) contributed to greater participation in paid work among women and children to fill household income gaps; cases of child labor were noted to have increased

Work-from-home advisories and virtual work practices benefitted individuals in formal employment (mostly men); those in the informal sector and operating businesses that require face-to-face interactions (mostly women) could not earn an income working from home

Chamas, which are typically dominated by women as avenues of peer support and financial empowerment, supported women through loans which were used to keep their small businesses afloat during the pandemic; while some women also sought loans through banks, such avenues are typically limited to individuals who have assets as collateral

-

How are values defined?

E.g., expectation on appropriate behaviour, attitude of influenceHow did gendered norms and beliefs shape the distribution of COVID-19 economic impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

Social norms and beliefs expect men to be financial providers within their households but the pandemic made it difficult for men to fulfil this social expectation. As men lost employment and women stepped in to support their households by seeking paid work, tensions were noted to have increased within families with men feeling demoralized by their limited ability to provide

In low income households, where men were unable to secure formal employment during the pandemic, women are noted to be breadwinners while men did little to support household income; this could be a result of norms that deter men from seeking feminized or devalued income opportunities that were available during the pandemic such as selling in the market

Social norms of mutual support and harmony within financial support networks such as chamas (peer support groups) and cooperatives were challenged by limited in-person meetings and economic desperation among members during the pandemic; some members made financial decisions without following established procedures. Some support networks collapsed due to reduced social cohesion and economic hardship among members

-

Who decides?

Power distribution & negotiation at household/ community levelHow did the power dynamics within the household shift due to economic impacts of the pandemic? Who made decisions regarding how to deal with the economic impacts?

Women’s greater role as providers in response to negative economic impacts of the pandemic likely increased their decision making power within households

In some households where families had moved to urban centers close the men’s place of employment, men made the decision to send their families to rural areas or villages to reduce the household cost of living

Corporate, religious, and civil society organizations provided temporary relief to residents through food donations and crop seeds to farmers among other economic programs; some initiatives targeted women

Cooperatives offered their members an opportunity to take out loan at better rates than banks at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic; some revised loan repayment instalments and repayment periods to help their members cope with the economic impacts of the pandemic. Decision of Cooperatives are made by their membership.

-

How is power structured?

Leadership opportunities, education, employment, ownership/inheritance rights, infrastructureHow did government institutions and law contribute to security impacts of the pandemic, and how did they attempt to address these impacts? Was there a balanced gender representation within related government structures?

Public health measures such as closures, curfews, social distancing and stay-at-home advisories resulted in loss of income and employment increasing food insecurity and levels of poverty; logistics of transporting goods disrupted supply chains for businesses

Work-from-home advisory only benefited those who had formal employment; this work arrangement was inaccessible to most people who required face-to-face interactions outside the home to earn an income

Police enforcement of public health measures contributed to fear that deterred economic activities for those who relied on daily wages for sustenance

The county government responded to the economic impacts of the pandemic and consequent public health measures by redirecting budgetary allocations to provide food relief, sanitary towels, and flood-related housing support to most-in-need families, the elderly, and people living with disability; over 30,000 families across 15 wards were supported through these initiatives

The gender and social services departments which took a lead in relief provisions to address effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and floods had a leadership team that was gender balanced

The county government suspended taxes for small informal businesses (approximately charged at 30 KSH a day). This provided relief to small business owners, especially women, but reduced the county revenue base; the national government also provided additional tax relief during the pandemic

To prevent misappropriation of food and other donations from non-government partner resulted in the county government requesting donors to deliver donations directly to beneficiaries, with county officials only accompanying them

There was an increased awareness on the need to invest in development initiatives aimed at creating economic opportunities at sub-county level; some people who had moved to urban centers for work moved back to rural areas during the pandemic due to lost employment and incomes

While the law states the right for equal employment opportunities regardless of gender, a gendered segregating in the labor market (men in the formal sector and women in the informal sector) can still be observed due to social norms and gendered roles

What were the security impacts of the pandemic & health measures? e.g., GBV, neighbourhood crime, police enforcement

-

What has what?

E.g. income, assets, information, knowledge (education), mobility, social networks, timeHow did gendered access to resources shape the distribution of COVID-19 security impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

Schools were considered a safe space for girls that reduced chances of gender-based violence and adolescent pregnancies. A layer of protection offered by school was lost following school closures; some were forced to stay at home with their abusers

It was noted that in some communities, insecurity cases such as robbery increased during the pandemic; gaps in the presence of police officers during curfew hours and young people who were out of school yet lacked economic opportunities was noted as contributing factors

-

What has what?

E.g., paid and unpaid labourHow did gendered labor and roles shape the distribution of COVID-19 security impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

Punitive enforcement of public health measures by the police made it difficult for market women to engage in business due to fear of, and, harassment by police; however, the police were noted to have been more harsh towards men and women

Security personnel were noted to have experienced burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic because of dependence on their service in the enforcement of public health measures; most security personnel are men

Income insecurity among health care professionals was notable during the pandemic as delayed wages and inadequate resources to respond to cases of COVID-19 contributed to labor action and strike

-

How are values defined?

E.g., expectation on appropriate behaviour, attitude of influenceHow did gendered norms and beliefs shape the distribution of COVID-19 security impacts and how people responded to these impacts?

Restrictions in some social and cultural practices such as disco matangas (funeral parties) and night parties during the pandemic was perceived as having improved security within communities

Greater presence of men within households during the pandemic not noted to have contributed to family conflict and gender based violence; married couples noticed faults in each other that they might have otherwise ignored if not for the close and frequent interactions

Some women risked their personal security by discharging themselves from quarantine centers to fulfil their family care responsibilities and for fear of infidelity by their husbands following their prolonged time away from the home

Strained relationships between adolescent girls and their parents were noted to expose the girls to situations that compromised their security such as seeking shelter or support from men who elicit sexual favors in return or assault them

-

Who decides?

Power distribution & negotiation at household/ community levelParents tried to restrict movement of adolescent girls outside the home following schools closures in an attempt to protect them from risks associated with adolescence pregnancy such as sexual assault and transactional sex

The police exercised punitive power in their enforcement of public health measures contributing to social stress and discord

-

How is power structured?

Leadership opportunities, education, employment, ownership/inheritance rights, infrastructureHow did government institutions and law contribute to security impacts of the pandemic, and how did they attempt to address these impacts? Was there a balanced gender representation within related government structures?

COVID-19 public health measures that restricted movement and closure of schools and avenues of social support contributed to situation of insecurity including domestic violence and gender-based violence

Reliance on police in the enforcement of COVID-19 public health measures created a sense of insecurity and fear in community due to the punitive enforcement

The county government ran a gender-based violence (GBV) center to support survivors including through counselling services, and encouraged reporting of GBV cases. A multisectoral approach was adopted including charitable children’s institutions, the Judiciary, the Policy, and various department of the Trans Nzoia County government (departments of children, gender and social services, health and policy)

The Trans Nzoia County’s supported the rehabilitation of street children by placing them in rescue centers before reintegrating them back to communities; the department of Gender and Social Services collaborated with the Judiciary, Police, and the Children’s Department in this work. The number of homeless children was noted to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic

The Trans Nzoia County government started discussions for a child protection policy during the pandemic and was ongoing at the time of this study (2023); the policy will outline how various actors can prevent child abuse and address issues of child safety

Methodology

Through research, we set out to assess risks, impacts, and resilience at play during the COVID-19 pandemic under the backdrop of ongoing Chamas for Change interventions. The Gender and COVID-19 Matrix was utilized as a research framework for data collection and analysis.

Developed by the Gender and COVID-19 Project (now, Gender and Public Health Emergencies global consortium), the Matrix supports analysis of how gendered power dynamics shape COVID-19 pandemic experiences. It includes domains that interrogate how gender interacts with access to resources, roles in society, societal norms and beliefs, distribution of decision-making power, institutional provisions, and how these subsequently shape differential risks and impacts of the pandemic across pre-selected COVID-19 topical domains.

Our analysis was informed by data collected through 11 focus groups and 11 key informant interviews— a total of 95 research participants. Focus groups included participants and nonparticipants of the Chamas for Change programme, men partners of women who had participated in the programme, as well as women and men community health promoters.

Geographical and social context

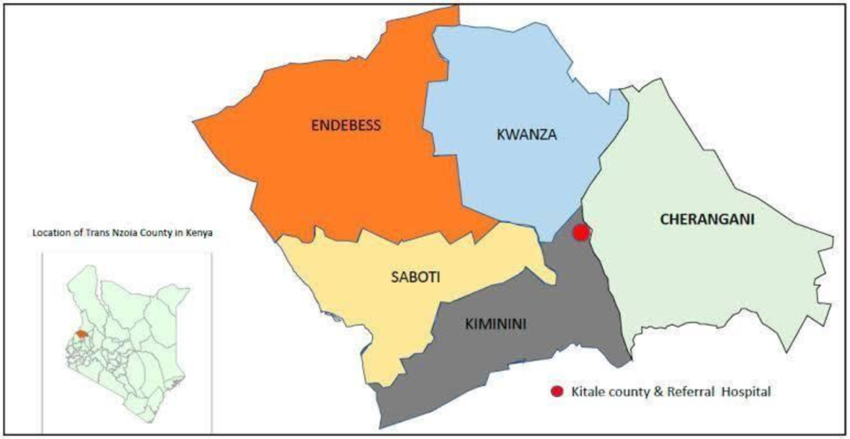

The Chamas for Change Matrix analysis was based on research conducted in Trans Nzoia County, Kenya. The County borders Uganda on the West and is divided into five administrative sub-counties (see Figure 1) which are further subdivided into 25 administrative wards. It has two main urban centers (Kitale and Kiminini towns) and one referral hospital serving patients across the county (the Wamalwa Kijana Teaching and Referral Hospital).

The population of Trans Nzoia is 990,341, with just over 500,000 being women (Kenya Population and Housing Census, 2019). Over 77 percent are below 35 years of age and 2.4 percent of the population lives with a disability. The County reports higher rates of poverty compared to national average rates. The main source of livelihood is agriculture: the County is said to be ‘Kenya’s breadbasket’ due to its large-scale production of maize (County Government of Trans Nzoia, 2023).

Gender roles in Trans Nzoia are produced and reproduced by norms and beliefs that designate women as caregivers and men as providers and protectors. This consequently limits women’s participation in paid employment and hence access to resources. Our study indicated potential shifts in gendered power relations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Map of Trans Nzoia County. Source: Ngera, Echaune, and Wamalwa, 2023.

*The Kitale County & Referral Hospital has, since 2024, been replaced with Wamalwa Kijana Teaching and Referral Hospital

Acknowledgments

The Chamas for Change research project team includes Julia Songok (Principal Investigator), Astrid Christoffersen-Deb (Co-Principal Investigator), Sammy Masibo (Co-Principal Investigator), Violet Naanyu, Michael Scanlon, Laura Ruhl, Julie Thorne, Justus Elung’at, Anjellah Jumah, Anusu Kasaya, Sheilah Chelagat, Sally Maiyo, John Hector, Samuel Mbugua, Abiola Adeniyi, Nadia Beyzaei and Alice Mũrage.

Alice Mũrage facilitated the adaptation of the Gender and COVID-19 Matrix.

A Community Advisory Board representative of various segments of society in Trans Nzoia (county system-level representatives and community members with lived experiences) offered community-based expertise throughout the project and shaped our research approach.

This project is funded through the International Development Research Center’s Women RISE.

Contact information

For inquiry about the Chamas for Change project: deanmedicine@mu.ac.ke or juliasongok@gmail.com

For inquiry about the Matrix: alice_murage@sfu.ca